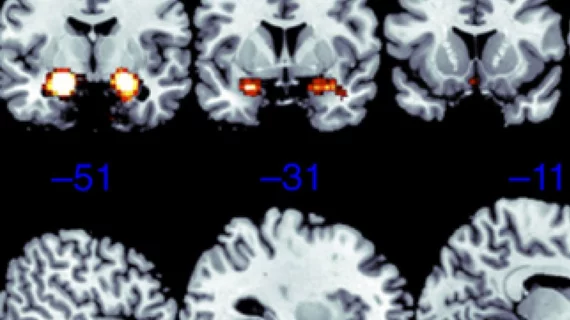

Medical studies continue to claim that scanning an individual’s brain inside of an MRI machine while they perform a specific task can help predict a person’s specific behavior.

However, a new analysis examining a number of these functional MRI (fMRI) studies finds such imaging-based measurements of blood flow are likely never the same twice, suggesting conclusions drawn about any one person’s brain cannot predict future behavior or mental health.

Examining the body’s largest organ through fMRI machines still remains effective for pinpointing the general brain structures involved in specific tasks, said Ahmad Hariri, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. But he noted that changes need to be made to keep his field alive and well.

“This is more relevant to my work than just about anyone else's," Hariri said in a Duke Today news item. "This is my fault. I'm going to throw myself under the bus. This whole sub-branch of fMRI could go extinct if we can't address this critical limitation."

For their analysis, published June 3 in Psychological Science, Hariri and colleagues pored over 56 papers based on fMRI data to determine how their conclusions held up across 90 experiments. They found that the correlation from one scan to another was “not even fair, it’s poor.”

They also looked at brain imaging information from 45 individuals included in the highly regarded Human Connectome Project. In six out of seven measures of brain function, the correlation was weak between exams performed four months apart on the same individual, the authors said.

Correlation from one test to the next was similarly poor in a New Zealand-based study in which 20 patients underwent task-based fMRIs twice, two or three months apart.

So what can be done? Hariri suggested collecting imaging information for at least one hour would be a start, rather than the typical five minutes. Establishing new tasks focused solely on producing reliable measurements of individual differences in brain activity is another approach, he added.

Russell Poldrack, an esteemed professor of Psychology at Stanford University, who had one of his own fMRI papers analyzed as part of Hariri and colleagues’ research described the findings as “a good wake up call.”

Poldrack, who has also been skeptical of fMRI-based studies for a while, according to Duke Today, did commend Hariri for taking action and noted brain connectivity mapping is not going away anytime soon.

"There's three things you can do," Poldrack said to Duke. "You can just up and quit, you can stick your head in the sand (and act as if nothing has changed), or you can dig in and try to solve the problems."